Published: 26th August 2025

Major energy transformations are nothing new. Older readers will have memories of what was dramatically called ‘C-Day’. C-DAY was shorthand for ‘Conversion Day ’. There were many C-Days across the UK during the late 1960s and early 1970s, when a specified district was changed over from manufactured town gas to newly discovered natural gas from the North Sea. It was a transformation that reshaped the nation’s energy system, touched every home and business, and carried both technical, economic and political challenges that remain relevant sixty years on.

North Sea gas was a game-changer

Town gas had been Britain’s dominant urban energy source for over a century. Manufactured by heating coal in municipal gasworks, it was used for cooking, heating, and even lighting in earlier decades. However, town gas was viewed as dirty and inefficient, plus it contained up to 17% carbon monoxide, rendering it hazardous, particularly in household settings. The discovery of vast natural gas reserves under the North Sea in 1965 by BP’s ‘jack up’ rig, Sea Gem, in the West Sole field was a game-changer. Predominantly composed of methane, natural gas was cleaner, safer, more efficient, and cheaper to produce in large volumes. Politically, it offered energy security at a time when oil imports were vulnerable to global market shocks. Unsurprisingly, the government of the day saw an opportunity to modernise Britain’s gas industry, cut pollution, and harness a domestic resource, with revenue opportunities for the Exchequer.

Town gas had been Britain’s dominant urban energy source for over a century. Manufactured by heating coal in municipal gasworks, it was used for cooking, heating, and even lighting in earlier decades. However, town gas was viewed as dirty and inefficient, plus it contained up to 17% carbon monoxide, rendering it hazardous, particularly in household settings. The discovery of vast natural gas reserves under the North Sea in 1965 by BP’s ‘jack up’ rig, Sea Gem, in the West Sole field was a game-changer. Predominantly composed of methane, natural gas was cleaner, safer, more efficient, and cheaper to produce in large volumes. Politically, it offered energy security at a time when oil imports were vulnerable to global market shocks. Unsurprisingly, the government of the day saw an opportunity to modernise Britain’s gas industry, cut pollution, and harness a domestic resource, with revenue opportunities for the Exchequer.

Further finds were made in quick succession, and by the end of 1969, gas was flowing ashore from the Hewitt, Lemann Bank, Dotty, Dawn, Deborah, Della, and Delilah fields, with many more to follow. This generated extensive EPC work for the delivery of gas platform jackets, top sides, tie-ins, pipe laying, and associated shore infrastructure for many BCECA members and their predecessor organisations, including John Brown, Brown and Root, and McDermott.

Not straightforward

Upstream activity continued apace; nonetheless, switching the nation to natural gas was not a straightforward exercise. Town gas and natural gas differ in chemical composition and energy content. Equipment designed for town gas would not operate correctly, and in some cases could be unsafe, if run on natural gas without modification. The scale of the challenge was considerable. First, the transformation required the construction of a national pipeline network capable of carrying high-pressure natural gas from offshore terminals to towns and cities. This led to the creation of a National Transmission System (NTS), which eventually stretched over 3,000 miles. Second, a huge number of premises had to be converted. A contemporary study noted that the process of conversion involved 650,000 commercial and industrial consumers and 13.5 million domestic customers. Finally, the switch over demanded planning, project management and meticulous execution on a national scale to ensure that no industry or community suffered a supply interruption.

Upstream activity continued apace; nonetheless, switching the nation to natural gas was not a straightforward exercise. Town gas and natural gas differ in chemical composition and energy content. Equipment designed for town gas would not operate correctly, and in some cases could be unsafe, if run on natural gas without modification. The scale of the challenge was considerable. First, the transformation required the construction of a national pipeline network capable of carrying high-pressure natural gas from offshore terminals to towns and cities. This led to the creation of a National Transmission System (NTS), which eventually stretched over 3,000 miles. Second, a huge number of premises had to be converted. A contemporary study noted that the process of conversion involved 650,000 commercial and industrial consumers and 13.5 million domestic customers. Finally, the switch over demanded planning, project management and meticulous execution on a national scale to ensure that no industry or community suffered a supply interruption.

The Gas Council, a central government body, created a conversion programme with military-style planning. Teams of engineers and technicians visited each property, sometimes twice — once to survey appliances and again to carry out conversion or replacement. The work was done region by region, following the gradual expansion of the new high-pressure grid.

The greatest peacetime operation in this nation’s history

The conversion programme began in 1967 and finished in 1977. At its peak, over two million appliances were converted each year. Around 100,000 workers — engineers, technicians, and support staff — were involved in this fundamental transformation of the UK’s energy infrastructure and much of the gas grid created still underpins the supply to this day. The exercise was, in the words of Sir Denis Rooke, chairman of British Gas from 1976 until 1989, “perhaps the greatest peacetime operation in this nation’s history.” When the Gas Conversion programme was declared complete in 1977, the total cost was reported at £600 million - equivalent to an economic project cost of circa £10 billion at 2024 prices. Funding came primarily from the gas industry, which was in public ownership at that time. There was no direct Treasury subsidy; instead, costs were recouped through gas revenues over time. Consumers indirectly paid for the change, but without any up-front charge. Since the gas industry was publicly owned, the conversion could be centrally planned and financed without the complexities of negotiating contracts between competing private operators, contractors and suppliers. Many would argue that this was a much simpler environment in which to make things happen.

The conversion programme began in 1967 and finished in 1977. At its peak, over two million appliances were converted each year. Around 100,000 workers — engineers, technicians, and support staff — were involved in this fundamental transformation of the UK’s energy infrastructure and much of the gas grid created still underpins the supply to this day. The exercise was, in the words of Sir Denis Rooke, chairman of British Gas from 1976 until 1989, “perhaps the greatest peacetime operation in this nation’s history.” When the Gas Conversion programme was declared complete in 1977, the total cost was reported at £600 million - equivalent to an economic project cost of circa £10 billion at 2024 prices. Funding came primarily from the gas industry, which was in public ownership at that time. There was no direct Treasury subsidy; instead, costs were recouped through gas revenues over time. Consumers indirectly paid for the change, but without any up-front charge. Since the gas industry was publicly owned, the conversion could be centrally planned and financed without the complexities of negotiating contracts between competing private operators, contractors and suppliers. Many would argue that this was a much simpler environment in which to make things happen.

Broad support from the British public and politicians

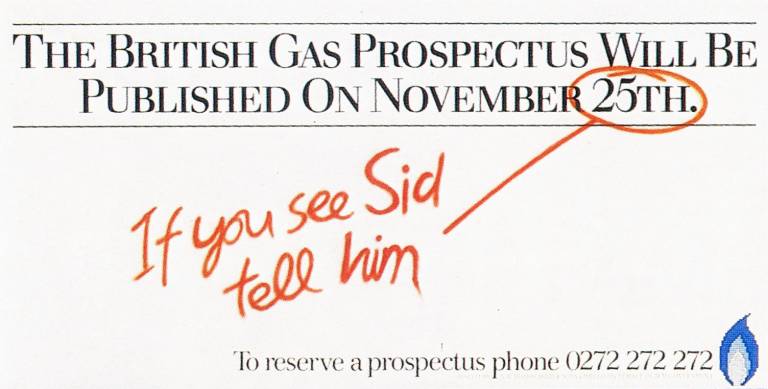

In the political sense, these were far less polarised times. The switchover had broad cross-party support because it aligned with several national priorities, including improved energy security via reduced dependence on imported fuels, support for domestic manufacturing and engineering jobs and better public safety and health. Inevitably, there were tensions. Trade unions sometimes protested over pay and working conditions. Some households worried about disruption or losing favourite appliances. Much of this was defused by extremely effective public communication campaigns, including TV adverts and local demonstration events. Even the dramatic flaring of excess gases in heavily populated urban areas during the switch over to natural gas often passed without undue concern or adverse comment.

In the political sense, these were far less polarised times. The switchover had broad cross-party support because it aligned with several national priorities, including improved energy security via reduced dependence on imported fuels, support for domestic manufacturing and engineering jobs and better public safety and health. Inevitably, there were tensions. Trade unions sometimes protested over pay and working conditions. Some households worried about disruption or losing favourite appliances. Much of this was defused by extremely effective public communication campaigns, including TV adverts and local demonstration events. Even the dramatic flaring of excess gases in heavily populated urban areas during the switch over to natural gas often passed without undue concern or adverse comment.

Different times – different solutions?

Half a century later, the UK is confronted with another energy transition — this time from natural gas to low-carbon alternatives such as hydrogen with associated carbon capture, storage and transportation. The similarities with the 1960s are striking. A national infrastructure overhaul is needed; it’s going to cost a lot of money, public buy-in will be essential, and safety and compatibility will again be key issues. But there’s a critical difference. Back in those times, the government played a central coordinating role. The Gas Council, a nationalised entity, managed finances, issued loans, and directed investment. The Gas Act 1965 raised borrowing limits to £1.2 billion, enabling large-scale financing. The privatisation programmes of the 1980s now make such ‘top-down’ interventions much more difficult.

Half a century later, the UK is confronted with another energy transition — this time from natural gas to low-carbon alternatives such as hydrogen with associated carbon capture, storage and transportation. The similarities with the 1960s are striking. A national infrastructure overhaul is needed; it’s going to cost a lot of money, public buy-in will be essential, and safety and compatibility will again be key issues. But there’s a critical difference. Back in those times, the government played a central coordinating role. The Gas Council, a nationalised entity, managed finances, issued loans, and directed investment. The Gas Act 1965 raised borrowing limits to £1.2 billion, enabling large-scale financing. The privatisation programmes of the 1980s now make such ‘top-down’ interventions much more difficult.

In addition, we are living in very different economic times. The 1960s shift delivered immediate safety and economic gains. North Sea gas provided substantial tax and royalty revenues for the government. Funding of conversion and infrastructure did not impact taxpayers directly; The Gas Council (later British Gas) obtained capital via commercial operations. By the early 1980s, its asset base was valued at ~£10.5 billion with capital liabilities under £400 million. Today’s energy transformation agenda is driven mainly by long-term environmental necessity, which has always been much harder to sell politically, and a glance at the news headlines suggests that this won’t get any easier in the short term.

Engineering contractors make it happen

Here at BCECA, we remain optimistic. The town gas conversion described here proves Britain can deliver a whole-system energy transformation in about a decade — in a very different era, and one without widespread automation and advanced computing power. Our predecessors made this happen, armed with slide rules. It shows the importance of effective planning and coordination, appropriate funding, clear lines of accountability and sustained engagement by government, private industry and the public.

Here at BCECA, we remain optimistic. The town gas conversion described here proves Britain can deliver a whole-system energy transformation in about a decade — in a very different era, and one without widespread automation and advanced computing power. Our predecessors made this happen, armed with slide rules. It shows the importance of effective planning and coordination, appropriate funding, clear lines of accountability and sustained engagement by government, private industry and the public.

Major energy transformations are nothing new. Engineering contractors have done it before, and they can do it again. The question is, how do we deliver the next energy transformation and continue the decarbonisation of the UK’s energy systems before it’s too late?

This will be the key talking points at BCECA’s 5th Annual Conference, which takes place on Wednesday, 8 October 2025, and continues with a series of online breakout sessions through November and December, with a report back in the House of Lords on 13 January 2026.

For more information and to register, visit: 2025 Conference Registration

Malcolm Crawford spent over thirty years in the UK engineering contracting sector, including senior roles at Amec Foster Wheeler (now Wood plc). He is currently BCECA's Conference Manager.

Andy Furlong is a content strategist at Cogent Content Ltd. Cogent Content provides communication and stakeholder engagement support to BCECA.

References:

A history of natural gas in the UK - Office for Budget Responsibility - July 2023

https://obr.uk/box/a-history-of-natural-gas-in-the-uk/

Fiscal Risks Report - Office for Budget Responsibility - July 2021

https://obr.uk/docs/dlm_uploads/Fiscal_risks_report_July_2021.pdf

History of the gas Industry - National Gas - website accessed August 2025

https://www.nationalgas.com/about-us/history-gas-industry

Lessons Learnt: Past Energy Transitions in the Gas Industry. Prof. Russell Thomas - A collaborative project between Wales & West Utilities, WSP and Northern Gas Networks - website accessed August 2025

https://www.wwutilities.co.uk/media/5331/lessons-learnt-from-the-past.pdf

The Manufactured Gas Industry Volume 1 - Prof. Russell Thomas - Historic England Research Report 2020

https://historicengland.org.uk/research/results/reports/8009/TheManufacturedGasIndustry_Volume1